Photo credit: California Department of Water Resources

Bloom or Bust: Navigating the Wild Waters of Harmful Algal Bloom Monitoring in the San Francisco Estuary

August 17, 2023

By Senior Environmental Scientist Tricia Lee

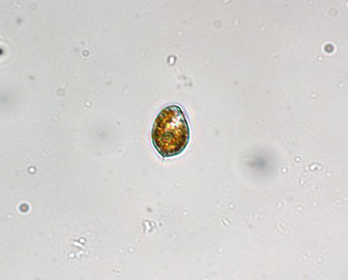

As soon as the weather starts to warm and the days start to lengthen, I keep an ear out for algal bloom rumors. A few weeks ago, a harmful algal bloom (HAB) in San Francisco Bay was reported and determined to be caused by the same HAB-forming organism, Heterosigma akashiwo, that bloomed last summer, resulting in massive fish kills. Although we have not yet seen that level of devastation from this current incident, the threat of HABs to San Francisco Estuary habitats persists. Despite the consistent presence of HABs in the Estuary, the science community lacks the ability to forecast conditions for HAB development like those created in other water bodies. This means that we can only deal with HABs in a reactive manner rather than having tools to proactively prevent HABs.

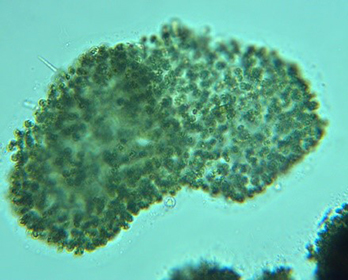

Freshwater HAB-forming organism Microcystis was first documented in the estuary in 1920, and coastal HAB organisms Pseudo-nitzschia and Alexandrium have been monitored by the state of California since 1927. The threat of HABs can come in many forms, for example, H. akashiwo, Microcystis, Pseudo-nitzschia, and Alexandrium produce different toxins that can cause a range of effects including skin rashes, liver cancer, and even death depending on severity and longevity of toxin exposure. The Delta Stewardship Council is funding a research project to investigate the aerosolization of toxins by Microcystis, a previously unknown exposure route for the Estuary. Additionally, HABs such as H. akashiwo can cause fish and other aquatic organisms to suffocate as the bloom organism can grow so large, it takes up all the oxygen in the water column.

Microcystis colony. Photo credit: Janis Cooke, Central Valley Regional Water Board

Heterosigma akashiwo. Photo credit: Kudela lab, UC Santa Cruz

Pseudo-nitzschia. Photo credit: California Department of Public Health Marine Biotoxin Monitoring Program

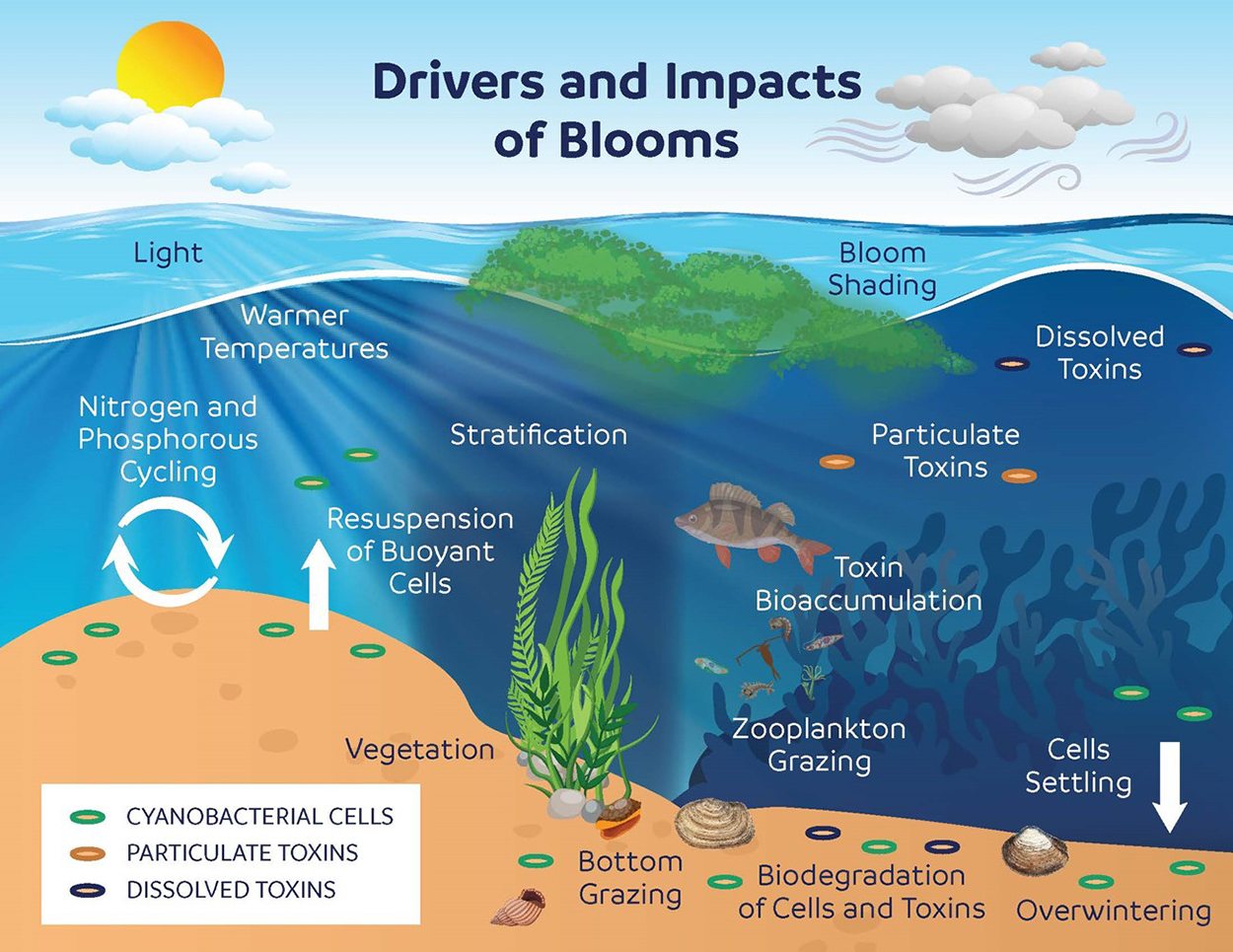

Myriad environmental conditions combine to develop a HAB, including temperature, water movement, and nutrient availability. In urbanized environments like the Estuary, nutrients are added to the water by wastewater treatment plants, runoff from agriculture, and upstream atmospheric deposition. As temperatures rise throughout the summer, so does the potential for a HAB to develop. As our population increases, the potential for humans to be adversely affected by interacting with HABs also increases. Additionally, as climate change continues to influence our natural world, we are facing more frequent conditions that allow HABs to develop, including longer and hotter summers. And although we only hear about algal blooms when they are noxious, beneficial algal blooms that feed the aquatic food web are spurred by the same mechanisms of temperature, nutrient availability, and water movement, making managing HABs particularly challenging.

Determining exactly what causes a HAB to form is a tricky question. We have seen HABs form under both drought conditions in 2022 and non-drought conditions this year. There have also been upgrades to a major wastewater treatment plant upstream in the Estuary to reduce nutrient discharges, a known driver of some HABs. You may be wondering, what are the long-term effects of these changes on the likelihood of HAB development? What is likely to happen with the current bloom in the Bay? Will it be as bad as the 2022 bloom that caused widespread fish kills? To answer these questions, we need a forecasting tool to track the drivers that cause HABs, which does not yet exist and for which we do not yet collect the right type of data.

The San Francisco Estuary lacks a consistent approach to monitoring HABs and conditions that drive their development, thereby leading to a lack of cohesive information for management decisions. In a companion blog, my colleague, Interagency Ecological Program Lead Scientist Dr. Steve Culberson, discusses the increasing amount of data available for the public to see what is going on in the Estuary such as satellite imagery that estimates cyanobacteria and chlorophyll-a amounts, proxies for bloom development. But we still need to be able to obtain this kind of data in a comprehensive, real-time manner for priority locations and tie these data to management actions. To address this gap and discuss the science community’s priorities for HAB monitoring, a multidisciplinary group held a HABs monitoring workshop that was hosted by the Delta Science Program in November 2022. It was clear from the needs of the community that approaching HAB monitoring needed to be taken in steps, and the first step is developing a HABs monitoring strategy that focuses on cyanobacterial HABs in the Delta. Although the HAB in the Bay has occurred two years in a row, one or more cyanobacterial HABs have recurred almost every year in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta since 1999, producing toxins that pose a threat to the aquatic ecosystem as well as human health. To cohesively respond to cyanobacterial HABs we must focus on a unified approach to data collection and information sharing, which is what our forthcoming HABs monitoring strategy hopes to provide a structure for. If successfully implemented, this can be a case study to then expand to the rest of the Estuary to get us closer to a HABs forecasting tool that will improve our ability to manage HABs for the protection of the Estuary as an ecosystem and as a home for millions of Californians. The HABs monitoring strategy is due to be released for public comment later this year. You can receive notices regarding the development of the HABs Monitoring Strategy by contacting us at collaborativescience@deltacouncil.ca.gov and subscribing to receive the Council’s email announcements.

As the science community keeps our collective eyes (real and satellite) on the developing bloom in the San Francisco Bay, we must also continue the work to expand our capacity to model and forecast HABs. This will allow us to move toward proactively addressing HABs rather than only having the tools to react to the deleterious side effects of a HAB after it has developed. In the meantime, you can help the science community respond to this HAB by reporting sightings of dead organisms you believe to be due to the San Francisco Bay HAB to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife through an iNaturalist project they have set up for this purpose.

About the Author

Tricia Lee

Tricia Lee is a senior environmental scientist at the Delta Stewardship Council, where she works to increase collaborative science on emergent water quality topics such as HABs and contaminants of emerging concern. Prior to joining the Council as staff in 2021, she completed a Sea Grant State Fellowship with the Council in 2017 and later worked in a variety of roles to optimize sustainable aquatic resource management including evaluating water quality near commercial shellfisheries for the California Department of Public Health and implementing the recycled water policy for the State Water Resources Control Board. Tricia received a Master of Science in Marine Biology from San Francisco State University at the Romberg Tiburon Center. When she's not working, Tricia enjoys paddleboarding, cooking from her garden, and spending time with her menagerie of pets.